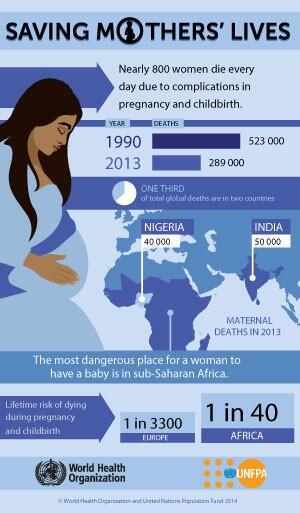

New data from the United Nations reveal that maternal deaths have declined by 45 per cent since 1990. Some 523,000 deaths occurred from complications in pregnancy or childbirth in 1990; in 2013, that number was 289,000.

Despite this progress, most countries are not on track to meet the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target on maternal mortality, which calls for cutting the maternal mortality ratio by 75 per cent by 2015.

Nearly 800 women continue to die every day from pregnancy and childbirth. Not enough is being done to prevent adolescent pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, HIV and gender-based violence, all of which endanger the lives of women and girls.

“Relatively simple and well-known interventions, like midwifery services and gender-based violence prevention and response, can make a huge difference if scaled up and coupled with investments in innovations, especially in the area of contraceptives,” said Kate Gilmore, Deputy Executive Director of UNFPA, the UN Population Fund.

Revealing figures

The new data, published in Trends in maternal mortality estimates 1990 to 2013 , comes from an inter-agency group that includes UNFPA, the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Division (UNPD) and the World Bank Group. The figures were produced through an academic collaboration with the National University of Singapore and the University of California, Berkeley.

The data, which come from dozens of studies and improved methods of estimating births and deaths, are considered more reliable than previous assessments.

The report reveals that just 10 countries account for around 60 per cent of all maternal deaths: India (50,000), Nigeria (40,000), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (21,000), Ethiopia (13,000), Indonesia (8,800), Pakistan (7,900), the United Republic of Tanzania (7,900), Kenya (6,300), China (5,900) and Uganda (5,900).

It also shows that sub-Saharan Africa is still the riskiest region in the world to give birth. Chad and Somalia have the highest lifetime risk of maternal death – 1 in 15 and 1 in 18, respectively.

Still, there are bright spots in the report.

Eleven countries that had high levels of maternal mortality in 1990 have already reached the MDG target on reducing maternal mortality. These are: Bhutan, Cambodia, Cabo Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Maldives, Nepal, Romania, Rwanda and Timor-Leste.

What more can be done?

Health systems must be strengthened, with quality facilities, personnel, equipment and medicine made accessible to all women. Comprehensive sexuality education and services for young people must also be made available.

Many efforts to improve health care are currently underway. UNFPA and its partners are working on the ground to train health workers – particularly midwives – and to distribute life-saving supplies such as clean delivery kits. UNFPA also supports voluntary family planning services, comprehensive sexuality education and emergency obstetric care.

But healthcare solutions are not enough. The human rights of women and girls must also be prioritized.

“More than 15 million girls aged 15 to 19 years give birth every year – one in five girls before they turn 18 – and many of these pregnancies result from non-consensual sex,” Ms. Gilmore stressed. Adolescent pregnancy carries a heightened risk of injury and death.

More accurate data are also needed; it is believed that only one third of all deaths around the world are recorded.

Still, with the release of this new data, more is known about how many women are dying, and more is also known about the reasons behind their deaths. This will help policymakers and public health officials design better interventions.

"Thirty-three maternal deaths per hour is 33 too many," said Tim Evans, a health director at the World Bank Group. "We need to document every one of these tragic events, determine their cause and initiate corrective actions urgently."